Hi guys! Holy Cow! Somehow life got crazy and six months slipped by without me even signing on to my WordPress account! During this time I have gotten many new subscribers and a surprising number of comments. Not to mention the visitation to my blog is higher than it ever was while I was actively blogging! So, I thought it was time to start blogging again, to let everyone know what has been happening with me, and to respond back to all you awesome people who keep reading despite my lack of recent posts.

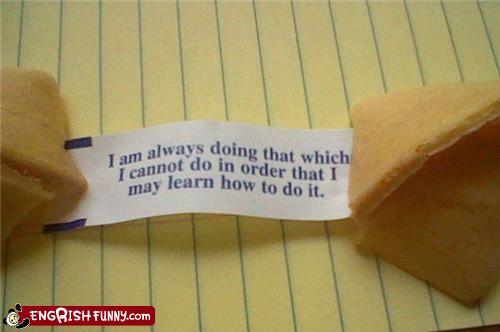

I am trying to think of where I was six months ago with the cello and it is hard. Every day that I practice I still think I am making no progress at all, that everything sounds just as awful as always. I think you guys all know about this problem. You’re so entrenched in what you are doing that it’s impossible to see the big picture, even when you try.

Laurène asked in a comment if I’d started vibrato yet. Goodness yes! A year and a half ago! This got me thinking about where my vibrato was six months ago. What a struggle it was!!! But now, it’s so natural that I don’t have to think about it! I hadn’t even noticed until now because it had become such a non-issue that I was freed up to think of other things instead of having to work so hard to achieve a mediocre vibrato. What a difference six months makes!

What else has happened? I am done with Feuillard. Finally! I miss it, to tell you the truth! What a wonderful book to learn from. I am working out of the Schroeder etude book. I also have been working for quite a while on a sonata by Breval. This one!

I had been wishing for so long to be working on a longer piece since that was never offered in Feuillard. I certainly got my wish. My teacher doesn’t ever let me just go through a piece and learn it quickly. Her instruction takes forever. Sometimes we won’t even work on it in lessons because she is refining some aspect of my technique (usually bowing) that she feels is holding back my performance of the piece as a whole. I got to perform the first part of the piece at a recital in December and will probably perform the whole thing at our next recital, which is usually in May.

Goodness, what else has happened? I took the second semester of music theory at the community college with the same awesome teacher I had for first semester. I decided not to take the third or fourth semester classes at this point because I’d gotten what I wanted out of the theory class – and more – which was to have a good foundation for what my teacher was talking about theory-wise in lessons. Also, the commute to class was getting a big cumbersome and I found it was eating away at time to practice. Plus, during these last six months, I’d gotten into cycling, got my first ever road bike, and have been busy bicycling my butt off! There is only so much time in the day and it’s impossible to fit in working, taking care of my mom, cello, class, cycling, and still have time for my husband! So, something had to give, and it was theory class.

For now, this is all. I am hoping to be a bit more active blogging, although I plan on updating every week or so rather than several times a week. Thanks again for all your readership!

Yesterday I was poking around on

Yesterday I was poking around on